Ramblings and Reflections on Queer Affinities for the Gothic and the Monstruous

— 2025Special thanks to my friend Lu for the background art

valeu queride <333

@luleane

For those who would rather listen:

I need a break from my graduation project. Not because I am uninspired, confused, lost or overwhelmed, but rather because I find that focusing on a single intellectual pursuit at a time can be limiting. Or rather, to focus solely on a single question at a time prevents one from identifying overlap, intersection, similarity or contrast between different areas of knowledge. Hence, I am taking this opportunity to materialize certain thoughts on the topics of queerness, filth and the gothic genre, which might not directly relate to my fine arts bachelor thesis, but are all tangential to it nonetheless.

My graduation project deals with issues surrounding the Image (with a capital because it refers to the Euro-US-American canon) and its role both as a memory and opinion shaper but also as a technology of death — How have (greater) Images, such as that of a country, community or geography, been used to justify violence against certain bodies? — I explore this topic using the history and memory (or rather lack thereof) of Nieuwe Holland, a 17th century Dutch settlement in Northeastern Brazil, and the project culminates in an exhibition of my research. Although I understood the framework of my investigation and knew what I wanted to achieve, I had been stuck on my methodology for a couple of weeks. Of course, the research would ideally speak for itself once exhibited, but I wanted its presentation to enhance the topics at hand while expanding the work’s subtext. It was only around early October that I came across a book that would be instrumental in the development of this project and subsequently inspire this essay.

When my friend Bianca (very talented graphics designer, go give her some love) left the Netherlands in July of this year she let go of a lot of personal items, particularly books. As an avid hoarder, I naturally took many of them for myself. However, it was only around late September that I took the time to calmly look through my new acquisitions. That’s when a certain book caught my attention: Brazilian Gothic is not for Beginners. This 60 page-long publication gathers three essays that present gothic readings of eminent Brazilian literature, more specifically of José de Alencar’s 1857 novel: O Guarani. The introduction which was written by the editors of the publication: Orlando Maaike Gouwenberg (curator) and Joris Linhout (visual artist), elaborates on their interest in the gothic lens and the reasons that led them to apply it to Brazil. One such reason is that the gothic, with its tendency to use the monstrous as an artifice to tension empathy while exploring processes of dehumanization, is a great lens through which one can critically think through colonial imagery. More particularly, how indigenous people, fauna and flora were subject to processes of “othering” at the hand of European settlers, and how said processes were used to justify violence against them. In other words, the often monstrous Image of Amerindigenous lifeforms created by settlers fuelled a European sense of superiority and control:

“By “Othering” these animals and people, in other words by making Brazil exotic, those Europeans fixed their positions towards life in the New World. By making monsters out of them (the wild animals as well as the Amerindians) they assumed full control over it. [...] this is a very good example of how the fantastic (the monster) is applied to a social and political situation (colonisation)”[1]

Now I must digress, as my goal for this essay is not to further my graduation project but to take a break from it instead. Having given you some context on my current interest in the gothic genre, its relation to the monstrous and subsequently the Image, I feel ready to hold your hand through my views on queer affinities for the gothic and why monstrosity and filthiness are my favorite forms of queer expression.

Everything starts with the time warp

On a random October afternoon, between couch-rotting, doom scrolling and cleaning the house, my flatmate Karina and I sat down to watch something. Earlier that week, she mentioned that she was feeling like rewatching The Rocky Horror Picture Show, and since it had been years since my last watch, I suggested we do exactly that. Upon finishing the movie, I realized it was just as sublime, provocative and oddly comforting as I remembered it.

The Rocky Horror Picture Show is based on a WestEnd theater production written by Richard O’Brien in 1973, which draws heavy inspiration from UK countercultures, more specifically from punk subcultures. For those who might be unfamiliar with this ultimate cult film, allow me to paint a picture:

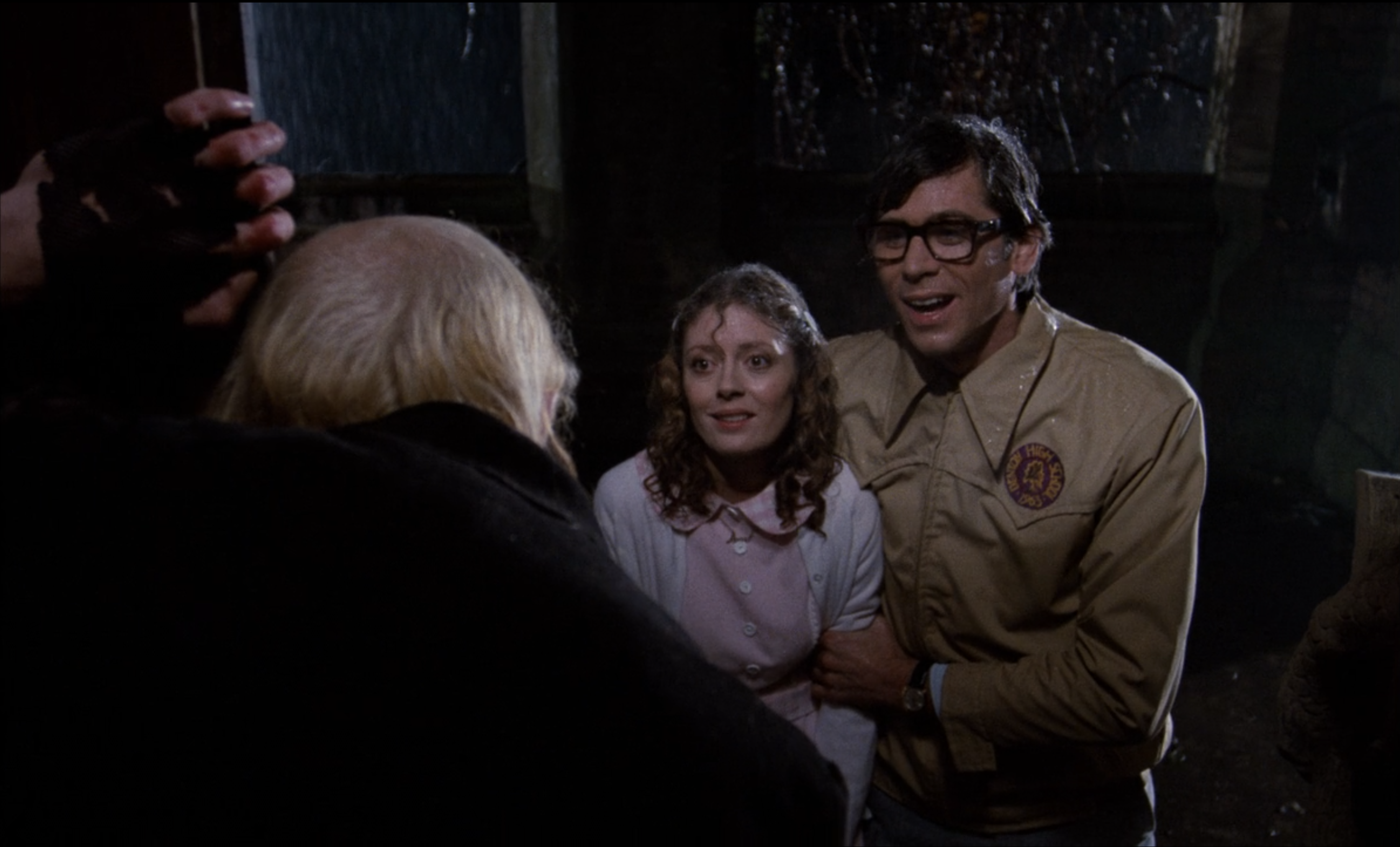

Brad (Barry Bostwick) and Janet (Susan Sarandon) are a recently married couple that get a flat tire in the middle of the woods. When looking for help, they come across a mysterious castle and knock on the door. They are greeted by Riff Raff (Richard O’Brien), the castle butler, Magenta (Patricia Quinn), the maid, and Columbia (Nell Campbell). A fast paced musical number ensues and by the end of it Brad and Janet finally meet Frank N Furter (Tim Curry), a transgender scientist (who is also an alien?) with plans to design and create the ideal partner: Rocky (Peter Hinwood). Viewers follow the chaos that ensues after Frank breathes life into his artificial hunk[2].

This rewatch reminded me of how much I love this film. Its gothic subversions, its perversions of gender and sexuality, its lustful show tunes, and above all, how all of these qualities make for a feature film that is a filth masterpiece.

Degeneracy as a gothic theme

Needless to say, The Rocky Horror Picture Show references the story of Frankenstein’s monster. A mad scientist (Frank N’ Furter) creates life (Rocky) in their laboratory; a pretty straightforward parallel. The original novel, written by Mary Shelley in the early 19th century, is considered a precursor of fin- de-siècle[3] gothic, with many gothic themes originating from Shelley’s writing. However, the gothic concept that is of greatest interest to the analysis I am proposing is that of degeneration, which represents a pillar of late 19th century gothic writings. The professors of english, and experts on the gothic genre, David Punter and Glennis Byron contextualize degeneration as a fin-de-siècle gothic idea in their book; The Gothic;

“The traditional values and family structures upon which the middle class had based its moral superiority were disintegrating, challenged by the emergence of such figures as the ‘New Woman’ and the homosexual. Gothic texts of the late 1880s and 1890s consequently come to be linked primarily by a focus on the idea of degeneration.”[4]

It is also worth adding that the concept of degeneration is influenced by Darwinistic developments. Theories of evolution gave rise to the idea that, if a species could evolve, it could also degenerate. Many European scientists and anthropologists confidently argued that certain humans could decline into a lesser form of the species, and that this decline, characterized by physical traits, led to immoral and criminal behavior. Scientists were also concerned that regular people could degenerate just by being in proximity to immoral individuals, in turn becoming criminals themselves. According to them, the exclusion of degenerates was justified based on their innate perversion, same goes for attempts to rehabilitate them. However, if we consider that the ones writing European legislatures then were predominantly (if not ALL) rich white-european supremacists, and degeneracy was measured through the criminal act, then, simply put, anything or anyone existing on the outskirts of the European colonial project was a degenerate. Needless to say that evolutionary anthropology would be used as the justification for all sorts of colonial white supremacist violence.

I believe that the relation between degeneracy and my original interest in the gothic is quite clear. Gouwenberg and Lindhout’s publication on Brazilian gothic is precisely an exploration of the monstrous amerindigenous as an allegory for the degenerate, or rather the unlawful; where representations of decadence become the European’s method to exert control and draw a line that can’t be crossed. By painting such an Image, violence and control over these bodies is justified on a false premise of moral superiority. Now, how does this relate to The Rocky Horror Picture Show?

In Faces of Degeneration, Daniel Pick, British historian and psychoanalyst, explains that accusations of moral decline were used against “the colonised overseas [...] but also to scrutinise portions of the population at home: the “other” was outside and inside”[5]. It became clear to me that Richard O’Brien’s choice to borrow from the gothic, as a queer author living in Britain when homosexuality was still criminalized, made perfect sense.

Richard O’Brien, who wrote the WestEnd musical production that inspired The Rocky Horror Picture Show, is a queer British-New-Zealander who moved to London in 1964, only a couple years before the Sexual Offences Act of 1967. This bill criminalized public displays of homosexuality and would be active until the turn of the century. Although I understand I’ve made quite the time jump, I believe that the idea of degeneracy still permeates. Especially if we consider that degeneracy is determined through the criminal act. Furthermore, the bill explicitely states that homosexual acts have “immoral purposes” and represent a “gross indecency”[6]. Thus, it is no wonder that Richard O’Brien was drawn towards the gothic when wanting to portray non-conforming gender and sexuality. The Gothic genre is inherently connected to the monstrous, and the monstrous is connected to the unlawful.

However, it is precisely the monstrous’ relationship to the unlawful that informs O’Brien’s subversion of Frankenstein’s tale.

The monster’s longevity

A popular interpretation of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein involves the understanding that the monster played no part in its creation, yet is demonized by those around it. The book also questions the doctor’s hubris and his disregard for the cycle of life. Shouldn’t he be the monster? As put by Gouwenberg and Lindhout in the introduction of their publication:

“As Frankenstein taught us, creating a monster brings responsibilities, a responsibility towards those who will have to face the monster, but even more towards the monster itself. Because the monster is only a monster in the eye of the beholder”[7].

With this in mind, I would argue that O’Brien subverts the role of scientist and monster by inverting them, thus creating a mirror image to British legislation then. If the sexual offences act determined that public homosexuality was illegal, then homosexuals, to the eyes of those around them, were monsters. It is no wonder that Frank N’ Further is characterized by their unorthodox and overtly feminine gender performance and fluid sexuality, whereas Rocky is a clean slate vulnerable to perversion. Afterall, Rocky is a white, blond blue eyed manly man, the epitome of masculinity, hence normativity, in a patriarchal context.

Furthermore, if according to Punter and Byron, classic gothic imagings are a mirror to middle and upper-class anxieties towards the “New Woman” and homosexuals, then O’Brien’s gothic reflects the middle and upper-class anxieties of the 70s instead. Indeed, the early 70s saw the birth of early punk, a subculture concerned with anti-consumerism, sexual freedom and provoking the status-quo, which led to a wave of moral panic across the UK. An example of this being the Sex-Pistols’ appearance on UK tea time television in December of 1976, which was met with stark criticism for their foul-mouthed lyrics and lewd stage presence[8]. So, the anxieties of cisheteronormativity are reflected in O’Brien’s choice to invert the classic characterization of monster and scientist, where the creator has a monstrous appearance rather than the creation. The fear of moral corruption is represented by Frank’s disposition to enact said corruption on all other characters.

Take Brad and Janet for example, the perfect cishetero suburban couple, who arrive at Frank’s castle frightful of its inhabitants but are seduced by them as the film progresses. Frank tries to sleep both with Brad and Janet, succeeding with Brad, so Janet, led by jealousy, sleeps with Rocky. The couple’s growing inclination towards the sexual makes them an allegory for changing social norms that went hand-in-hand with counterculture movements concerned with sexual freedom, such as punk.

Nonetheless, unlike classic gothic texts that offer a resolution where monstrosity is dealt with and often annihilated, The Rocky Horror Picture Show doesn’t. Take Bram Stoker's Dracula for example, where the count represents lust, sexual depravity and a fear of Eastern European foreigners. By the end of the novel, Dracula is vanquished, and along with him, the anxieties he represents. But the horror musical film, towards the end, twists into a conflict between Frank and the castle’s employees instead of offering an ending where the sexual depravity is exterminated. One of the film's final frames even shows Brad and Janet leaving the castle still adorned with corsets, high heels and gartered fishnets. Their depravity remains intact.

This is, in my humblest opinion, the reason why The Rocky Horror Picture Show was a critical flop when it made its mainstream debut in 1975. Although I haven’t gone after this information, I imagine that the film being a musical made it eligible for daytime programming. However, daytime runs were, and are often still, reserved for family friendly content. Let’s just say, the average US American was not ready for the film’s libertinage. After its release the film only circulated for a few weeks before being removed from theaters across the US.

However, the film had conquered a loyal fanbase in LA who regularly filled out cinemas to rewatch the horror musical. This gave marketing executives the idea to run the film as midnight screenings in New York, which proved to be an amazing success. This same strategy was expanded to the rest of the US, and let’s just say that nowadays The Rocky Horror Picture Show holds the record of longest period of constant circulation, and is still being screened in cinemas around the globe[9].

I believe much of this success is owed to O’Brien’s choice for gothic sensibilities and his subversion of the genre, which hypnotized other queer people such as himself. Those existing outside cishetero normativity and “othered” by patriarchal hegemony, could see themselves reflected in the unapologetic transgressions, whether sexual or gendered, portrayed throughout the film. A gothic motion picture that isn’t concerned with resolving monstrosity, but rather normalizing it as the movie progresses. I find that it’s no surprise the film thrived once it was moved to the midnight session, afterall, most queer gatherings have historically happened in nightlife spaces. Our community organized in the dark, away from bigoted glares. Think of historical places such as the emblematic Stonewall Inn in New York, or one of my personal references, Clube Alaska in Rio de Janeiro, but also your local queer bar or club. Under the protection of the gloom, monsters gathered.

In defense of our transgressions

At the turn of the millenia, the British Sexual Offenses Act was modified and ceased to criminalize public homosexuality. The early 2000s was also a moment of legislative change for many countries, marked by the legalization of gay marriage. In April of 2001, the Netherlands became the first country to officially legalize same-sex matrimony. Then came a wave of new civil rights for trans and gender non-conforming people, with many Western countries allowing citizens to change their documents to reflect their actual gender identity for example. In essence, we stopped being monsters. However, if the monster exists outside the law and the patriarchal-capitalist system, becoming human requires that we mold ourselves to the system.

Now, corporations had an interest in monetizing representations of the LGBTQIA+ community. Such representations became increasingly sanitized, portraying a queerness that is not actively challenging the binary patriarchal mindset. Parades which used to be a site of protest were co-opted by corporate sponsorship. Cops stopped rounding up pride marches and started to escort them instead. Multinational streaming platforms such as Netflix, Amazon Prime or Disney plus started producing LGBTQIA+ content but, despite their depictions of gender non-conformity and sapphism, they often fail to make media that isn’t centered around cis-gay men. Think the popular show Heartstopper, which depicts an array of LGBTQIA+ identities although its plotline constantly revolves around the two main characters — a cis-gay couple. The show makes little to no effort towards de-centering men from its narrative. The Pride parades and series are but disparate examples of how we were pacified, or even in some cases, co-opted through the consumption of our own identities. By reselling us queer identities, corporate overlords were able to dictate what said identities should look like and how they should operate in society. The mainstream representations of sexualities and gender were constructed as to not challenge the binary patriarchal system, hence why most mainstream queer media will focus on cis characters that uphold the binary system rather than challenge it.

Consumers, unlike monsters, accept the system if consumption is its leading premise. I don’t want to delve much further into this, as I believe the topic of LGBTQIA+ consumption of queer identities under capitalism calls for an essay of its own. Instead, I will conjure the words of Brazilian artist Francisco Hurtz as seen in an instagram post by homocomunist:

“Gays who do not have access to consumption will not have dignity or a full gay life experience in neoliberalism. The culture of diversity is a way to reinvent capitalism, giving more color to the form, so that it continues to function in the old way. The liberal market used to sell products, then experiences, and now it sells causes and social justice because apartments are already full of stuff.”

To stop being monsters we had to purchase our human-hood. I do not want to use the word humanity here because, if anything, these processes made us more inhumane by shrinking the gap between us (particularly white queer people, such as myself) and our oppressors. Queer people that stand closer to normativity started attacking bodies more dissident than their own. An example that comes to mind is a post on the social media platform X, or rather the reactions to it. Brazilian user Nico (he/they) — @nivo1as — shared a side-by-side comparison of him in high school and now. On one side we see an average looking feminine presenting person and on the other a person sporting harnesses, piercings, a mullet and tattoos, which contribute to a less gender-specific appearance.

His post sparked a wave of hate comments with queerphobic implications. Users questioned his decision to alter his appearance, calling him ugly, grotesque and unattractive (sounds familiar?). What was most appalling to me was that many of the haters were also LGBTQIA+ and that they made distinguished efforts to separate Nico and alternative sub-cultures from themselves. Some go as far as to explicitly say to not group them with these “aberrations” and saying that they support the “return of asylums for the mentally ill”. The post now has surpassed over 60 million views and reached an international audience that was no less hateful than the initial Brazilian bigots. This is just one example to illustrate the extent to which we, as a community, have been sanitized through the commodification of our lifestyle. Nico does not look like the normative queers from mainstream media, and they were demonized for it. (in another post he says he took advantage and monetized his account and is making bank out of the hate; for the brightside)

The sanitization of homosexuality is what urged me to write this reflective piece, what led me to start exploring the history of the monstrous, the filthy, the gothic and to identify why I, as a queer person, felt like they represent us better than most queer media nowadays. I believe we, as a community, have a great problem on our hands and should acknowledge that many of us are turning their backs to queer sub-cultures. I would argue this suggests a lack of understanding of queer history and political struggle. An unwillingness to acknowledge that, before de-criminalization, we were all part of a sub-culture, independent of specific sexual or gender identity. All sexual and gender dissention was monstrous, no matter what the perpetrator looked like or where they stood with regards to normativity.

Hence, I would like to propose that we bring filth, decadence and monstrosity back to the forefront. I would like to propose that we champion gore. I would like to propose that we make art that expands on what it means to be queer rather than media that standardizes the gay identity. I would like to propose that monsters are the best possible role models for us, that they can teach us how to reclaim our dissidence through pride in the qualities that made us outcast.

I’ve always had a deep love for all things gothic and monstrous. When I was younger I was particularly obsessed with witches. I would collect figurines, dolls and posters of sorceresses, I would brew make-believe potions in glass jars and would watch my Sleeping Beauty cassette on a loop, always skipping ahead to Maleficent’s scenes. There’s a certain comfort, especially as a queer kid, in surrounding yourself with icons that are powerful despite being outcast. For me, a kid that got picked on for my queerness (particularly my femininity), the witch represented the possibility of being cunning and powerful despite being an outcast. Despite being hated. I guess I envied their ability to overcome the glaring looks, their love for monstrosity, their embracing of it. There’s a scene from a children’s cartoon that I remember vividly, where a witch looked at herself in the mirror and despite her wart covered face, balding head, crooked nose and protuberant joints, she smiled and blew a kiss at her reflection before flying out of the window. I unfortunately do not remember the name of the cartoon, but this scene remains. I will always remember that, for this animated witch, the qualities that could justify her monstrosity and filthyness, were things she cherished in herself. I think that we, as queer people, often have to learn to do the same.

Some recommendations:

All is not lost, filthy queer media still exists. I wanna leave a couple of recommendations of contemporary media by queer people that champion filth and the monstrous:

The Boulet Brothers Dragula — a televised drag competition with a focus on the horror genre. The competition champions three pillars through their main challenges: glamour, filth and horror. The show is very inclusive, often casting drag artists that exist beyond the commodified aesthetics of feminine drag done by cis gay guys (yes I’m looking at you RuPaul…), such as drag kings, afab performers and drag creatures.

Mamántula (2023) — A film by Spanish director Ion de Sosa which follows a detective trying to solve a series of lewd murders committed by a monster that disguises itself as a gay man with a thirst for giving blowjobs. I saw this screened during the International Film Festival of Rotterdam and fell in love. The movie has its flaws but the concept and plotline of the film made up for that in my opinion.

Les Demon de Dorothy (2021) — Directed by Alexis Langlois, the film follows the story of Dorothy, a lesbian filmmaker working on a piece of sapphic horror. After her producers suggest she should tone down her film and make it more mainstream, her demons (literally) emerge.

I am slowly building up my references for contemporary queer media dealing with the monstrous and would love to get some recommendations if you, the reader, would like to send me some (jpedropascoa@gmail.com) <33

[1] Orlando Maaike Gouwenberg and Joris Lindhout, “An Inquiry into the Presence and Habituation of a Brazilian Gothic,” essay, in Brazilian Gothic Is Not for Beginners (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Capacete Entretenimentos, 2012), 03–07.

[2] The Rocky Horror Picture Show (Twentieth century fox home entertainment, 2005).

[3] Fin-de-siècle: expression borrowed from French that means “end-of-century”, used mainly to refer to England at the turn of the 19th century and early 20th century.

[4] David Punter and Glennis Byron, The Gothic (Oxford: Blackwell, 2007).

[5] Daniel Pick, Faces of Degeneration: A European Disorder, c. 1848-1918 (Cambridge, GBR: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

[6] Sexual Offences Act 1967, c.60. Available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1967/60/contents (Accessed: 29/10/2025)

[7] Orlando Maaike Gouwenberg and Joris Lindhout, “An Inquiry into the Presence and Habituation of a Brazilian Gothic,” essay, in Brazilian Gothic Is Not for Beginners (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Capacete Entretenimentos, 2012), 03–07.

[8] “Punk and Anarchy in the UK,” Museum of Youth Culture, May 8, 2025, https://www.museumofyouthculture.com/punk/.

[9] Gregory Wakeman, “‘The Rocky Horror Picture Show’ Started Out as a Critical Flop. Fifty Years Later, the Beloved Film Is a Cultural Phenomenon,” Smithsonian Magazine, September 25, 2025, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-rocky-horror-picture-show-started-out-as-a-critical-flop-fifty-years-later-the-beloved-film-is-a-cultural-phenomenon-180987393/.